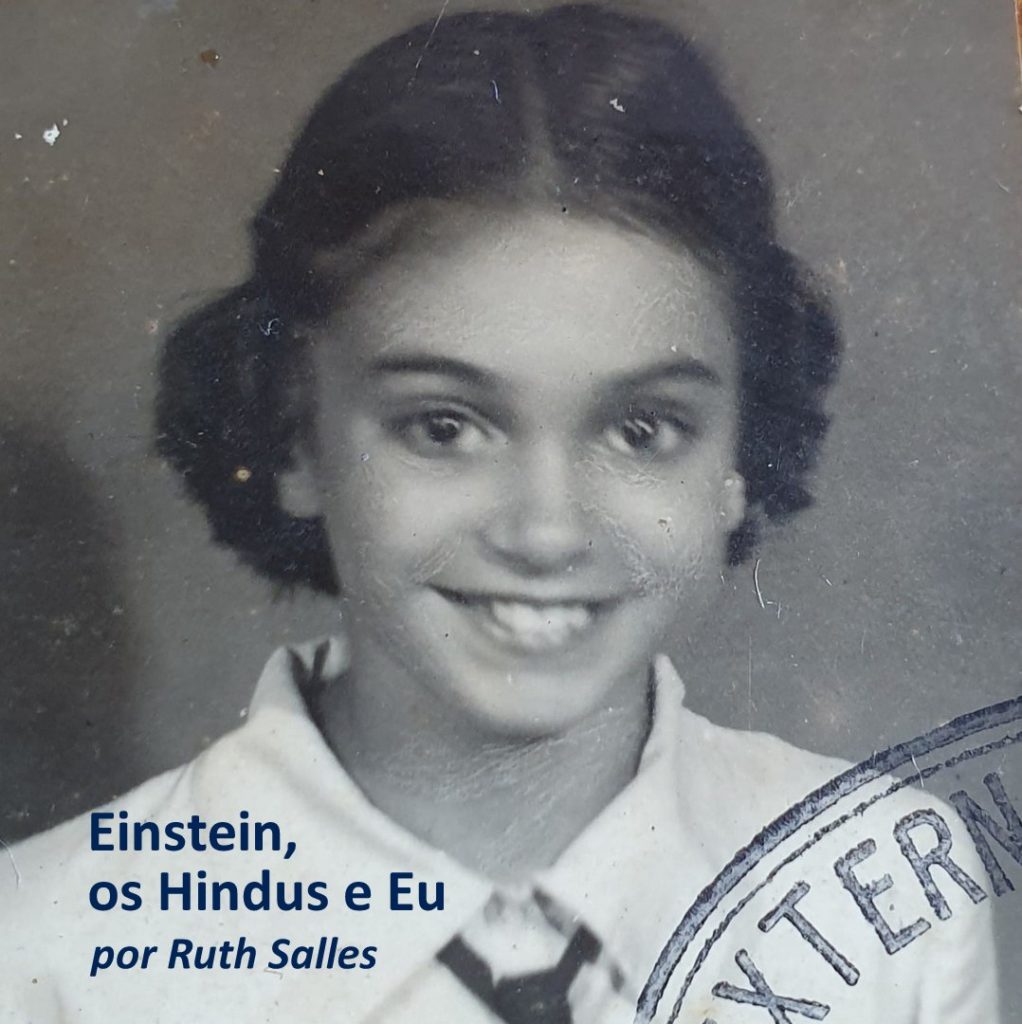

Simplicities and complications

by Ruth Salles

My maternal grandmother, the teacher from São Paulo, Carolina Carlos de Toledo, married the teacher from Rio de Janeiro, João de Deus de Mello e Souza, and was, at the end of the 19th century and in the beginning of the 20th century, the teacher at the Escola Pública de Queluz, in the Paraiba valley.

I say “the teacher” because she was the only one, because all the classes of the Primary Course at that time worked in a single room, which was simply the room in my grandmother's house. And she, alone, taught all classes simultaneously, with two children aged eight and six helping to distribute and collect notebooks, plus a baby in a rocking crib that she moved from time to time between classes. Two other small children were playing in the backyard, and there were also two older daughters who already lived in São Paulo, with relatives on their maternal side, and were attending the Escola Normal da Praça da República, and another son who was studying in Rio, at the time “ Gymnasio Nacional” (today “Colégio Pedro II”), as an inmate and under the care of relatives on the paternal side.

Classes ended at four o'clock in the afternoon, but sometimes, if the baby in the crib wasn't crying, my grandmother's conversation with the students would go on and on, until, at four-thirty, the housekeeper, without any ceremony , opened the door to the living room and called out: “Dona Sinhá! Dinner is on the table!”

After dinner, the kids were still playing on the sidewalk until it started to get dark, when the street lamp lighter came to do its job, unless there was moonlight. With a full moon the lamps were not lit. The city thus saved gas; But if a cloud covered the moon, night owls were at risk, and it was common to fall over animals that liked to lie down in the middle of the street – as was the case with the “Comet”, a traveling salesman, who had rolled down the ravine. of the Paraíba River, escaping from falling into the water, having stumbled at night on a sleeping ox.

It was at this time of dusk that my grandmother received visits from women seeking relief from her ailments. Let me explain: in Queluz there was no doctor; in serious cases, the train chief – when the train was heading towards São Paulo – would warn the doctor in Cruzeiro, and he would take the “fast” back. In simple cases, there was the pharmacist in Queluz, who sold potions and medicines, ointments, etc. dressings, which she grew in the backyard.

But sometimes this simple life of the teacher could get complicated in a minute. And now I give the floor to my late mother – the eight-year-old daughter who helped in the class, and who later was also a teacher and school principal – transcribing here one of the chapters of her Memoirs:

ONCE THERE WAS A COW

But it wasn't just any cow. She went in and out through the front door of her owners' house and walked her corpulence through the streets and squares of Queluz, where she was known and respected. Every morning, after fulfilling her primary duty, which was to feed her calf and provide milk for her owners, she would go out, escorted by a urchin, to graze, or, in more elegant language, to feed as she pleased in a vast field at the entrance or exit of Queluz. Between three and four o'clock in the afternoon, she would return with her companion, enter the living room door and go to enjoy the company of the calf and sleep without worries.

A curious person will ask:

– Why did the cow use the social entrance of the house? I clarify. The entrance was social, but it was also private for the cow, because what there was on that stretch was a series of one-story houses, facing the street, joined one to the other, with a door leading to the sidewalk and another at the back, facing the street. the backyard.

We were neighbors of the Coelhos, owners of the cow, and I was afraid of her. It was a drama for me: living close, a wall and a half, to an animal that everyone said was tame and peaceful and didn't have the courage to approach him. It was big and had horns. His whole appearance terrified me. The result is that at that time – the year 1901 – I, who was only eight years old, could not even calmly enjoy the “dawn of my life and my dear childhood”, as Casimiro de Abreu said, because I was afraid of a cow.

Now, one summer afternoon, to better air the room, I left the front door open. Class was almost over when we heard a thud inside the small hall that led to the classroom. We looked, and then the shouting and confusion started. The cow had missed the door and there it was, almost inside the room. The girls were screaming, myself included, and my mother's baby, with that noise, began to cry aloud. Mother, distressed, tried to calm us down. Fortunately, the careless brat came to the rescue, pulling the animal by a rope attached to its neck. But it was difficult, in the small space of the vestibule, to force the cow to perform a 180 degree rotation and leave. She even had to go around inside her own room, which increased the children's fear and screaming.

From then on, I was careful not to leave the door open for airing. I preferred heat to cows. A few years later, my knowledge was enriched with the subject of atavism and its consequences. I thought the theory was great. Atavistic fear! It is so easy for us to transfer the responsibility for our weaknesses and imperfections onto the shoulders of a distant ancestor! With a little imagination and even reasonable logic, I could formulate this theory: Mom was a Toledo; Toledo remembers Spain, and Spain remembers bullfighting. I imagine a distant Toledo ancestor, strong and daring, who decided to be a bullfighter. And he encountered a stronger and more daring miura who knocked him out. This is the reason for the fear that came from my descendants and embedded itself in my humble person.

Throughout my life I've been acquiring various fears: zigzag cyclists, decrepit elevators, flying cockroaches and other minors. But I remain true to my childhood fear. Atavism is not discussed.”

(Chapter 11 of the memoir “De Longe Vem”, by Julieta Mello and Souza Miranda.)

***