Human development in seven years

by Rubens Salles

Although the human being is born complete in its structure, with body, soul and spirit, and with the psychic capacities of thinking, feeling and wanting, the development of each of these elements takes place in well-defined stages. Anthroposophy divides the development of man into periods of approximately seven years, the seven years.

Within these periods there are gaps between individuals and between the sexes, but even so it makes sense to consider them. Until the age of 21, when our physical development is complete, the soul and spirit are constantly adapting to the possibilities offered by the physical body. According to the anthroposophical view, from the third seven years onwards there is a greater development of the qualities of the soul until the age of 42, which will be the basis for the greatest development of the human being, the spiritual, which takes again 21 years, from 42 to 63 years. , when he starts to live as a fully present being, in a cycle of plenitude and serenity. It is with this vision of human development that Waldorf Pedagogy designs education.

The characteristics of the sevens

| Setenniums | Development focuses in each seven years | |

| 1st | from 0 to 7 years | want |

| 2nd | from 7 to 14 years | to sense |

| 3rd | from 14 to 21 years old | think |

| 4th | from 21 to 28 years old | sensation |

| 5th | from 28 to 35 years old | reason |

| 6th | from 35 to 42 years old | consciousness |

| 7th | from 42 to 49 years old | courage |

| 8th | from 49 to 56 years old | internalization |

| 9th | from 56 to 63 years old | wisdom |

| 10th | over 63 years old | fullness |

Source: Steiner 2007 – Our organization

We can characterize the first three seven years as follows:

1st septenium – The period between birth and the change of teeth.

2nd septenium – The period between the change of teeth and puberty.

3rd seven years – The period between puberty and adulthood.

The long period required to prepare the human being for life is unparalleled in the animal world because it has an individual spirit, an I that must learn for many years in living with other men.(1)

We know that in the contemporary world man needs to be predisposed to learn throughout his life, and that is why it is essential that his education grants him this stimulus. However, a fundamental concern of Waldorf Pedagogy is that each stimulus reaches the child at the most appropriate time, depending on their development and their natural readiness to take advantage of it in the most spontaneous, efficient and healthy way. Human development has its own needs, stages and moments, just like a plant, which will not grow faster if pulled by the leaves.

the first seven years

“What is sublime and grandiose in the contemplation of children is the fact that they believe in the morality of the world, believing with this that one can imitate the world.” Rudolf Steiner

Photo: Waldorf School Yellow House

The moment of birth signifies the definitive union between the body and the soul and spiritual elements of the new individual. At birth, everything in the young child is related to his body and his vital forces, and his soul capacities to want and feel are deeply integrated. His consciousness is very reduced and his will very strong. When a baby cries and kicks because he is hungry, his feeling is acting in unison with his wanting, his will to act. First the child wants to know his own body, and then the external world around him. Unconsciously, she gradually takes possession of her body and acquires more skill and dexterity.

Thus, in the first years of life, this child's desire, which springs from his deepest needs, is the gateway to learning, which the child himself shows us through his reactions. When she imitates, or tries to imitate, what her father or mother is doing, she is showing us that this is the path for her development at this stage. Frans Carlgren and Arne Klingborg, explain that “for the child imitation is as important as breathing. The child breathes in the sensory impressions, and the imitation follows as the expiration.”(1)

Although we do not keep a conscious memory of the first 3 years of our lives, it is a fundamental phase for our formation, because in this period the child's sensory impressions have a direct shaping effect on their vital forces and their body. We are then greatly influenced by the environment in which we live and the people we live with, while we develop the fundamental skills of walking, talking and thinking.

At the end of the first year of life, the child acquires an upright position and learns to walk, conquering the physical space in its verticality, with its 3 dimensions: up and down, right and left, front and back. From this moment on, a new phase begins, which is language learning. The child learns to listen and speak and with the mastery of the language conquers the social space, between the Self and the next. With the conquest of the social space, he then begins to develop thinking, and then he perceives himself as an individual.

The child's perception is an active process, based on his interest in the outside world. For the impression to be transformed into perception, something is put into activity, from within, that leads it to meet the external impression. A child with an intellectual disability receives the same number of impressions from the outside as a normal child, but does not show, or has, on a reduced scale, an active interest in the external world. Lievegoed considers that “this active interest still results, in the small child, from a need, and not from a conscious will, as is possible at an older age.”(2)

Due to the fact that, at this stage, everything in the child's body is being formed, the influences that emanate from the social environment have profound effects on their physical and psychic organization, effects that will influence them throughout their adult life. In this sense, it is interesting to consider the case studies of children who in early childhood were raised isolated and living more with animals than with humans. These children, when found, practically did not speak, did not know how to smile and had acquired the habits and postures of the animals with which they lived. A child can only learn to walk upright if there is another human being who walks to teach him. This illustrates very well how far the impact of the environment can go on the formation of a human being, and demonstrates that without human interaction there is no humanity and there is no individual. For Malson (apud Luca Rischbieter) the conclusion is clear: “It will be necessary to admit that men are not men outside the social environment, since what we consider to be their own, such as laughter or smile, never illuminates the face of isolated children. ”. According to Craemer, “every human being is born with the seed of laughter, but for it to germinate, it needs to be 'watered' by the love of another human being”.(3)

At this stage, we consider that all education is a physical education, because all soul-spiritual education in the child is physically active. The lack of care at this stage of the child's life can generate disturbances in their health in the future, through metabolic, gastrointestinal and nervous diseases. As the child does not have a developed intellect, he cannot raise to a level of consciousness what he receives from the world and elaborate something. Thus, what he receives from the world is quickly incorporated into his organic constitution. Until the change of teeth, the child is really configuring his organism, and the most important thing is that he feels confident within his corporeality. She needs to be able to run, jump, climb, balance and feel good in her body.

“Exactly in the same way that speaking arises from walking, from groping, from human movement, thinking arises later, from speech. And it is necessary that, during the auxiliary orientation for the walk, we imbue everything in love; that during the learning of speech – because the child internally imitates what is happening around him – we dedicate ourselves to the most solid truthfulness; and that, in this way, we make clarity predominate in our thinking around the child, so that the child, being integrally a sensory organ, reproduces internally, in the physical organism, also the spiritual element with which it can extract correct thinking from speech”. (4) Rudolf Steiner

With regard to the impact of education on the future health of the child, it is important to consider

some polarities between the child and the elderly, in the table below:

The newborn and the elderly

| Newborn | Elderly |

| maximum vitality | low vitality |

| Soft, elastic, formable body | Dry, hard body |

| body with more water | Body with less water |

| Strong vital and vegetative functions | Reduced vital and vegetative functions and subject to pathological states |

| Conscience, intellect and other weak psychic qualities | Very strong conscience and intellect (provided they are not hampered by physical weakness) |

Source: Lanz 2009, pg 17 – Our organization

There is great care in Waldorf Pedagogy not to “age” children. When analyzing the picture above, we remember that life is directly linked to water, as we have already seen that mineralization is the opposite of life. Our aging is the defeat of our vital and vegetative forces for the mineralizing forces, which dry and harden our organism, and this reduction of our vital functions occurs in parallel with the increase in our consciousness and the strengthening of our intellect. Anthroposophical studies, whose details go beyond the scope of this work, indicate that, when education accelerates the child's intellectualization process, it is consuming vital forces that will be lacking in adult life. We will talk a little more about the relationship between education and health in the chapter on Education, Health and Lifestyle.

the world is good

In Waldorf kindergartens, the main message that is sought to convey to children in the first seven years is that the world is good. The environment for children must be very peaceful and loving, and the teacher's behavior must be worthy of being imitated by children.

The small child is characterized by being totally open to the world. Everything that comes from him she accepts with boundless confidence, without soul resistance, and in her naivete she experiences good and evil indistinctly. As Lievegoed observes, “It is through imitation that it learns the things, appropriate or inappropriate, that constitute human behavior. It is by a more subtle imitation that she creates the foundation for her future morality.”(5)

This openness to outside influences is unparalleled in any other phase of life. The child wants to imitate, and it is through imitation that he will learn what is good and what is bad. Unconsciously, he absorbs the impressions he perceives around him, and in this way he shapes his way of speaking and behaving. She is permeable to the most diverse influences of the environment and, as a large sensory organ, perceives the entire emotional climate that surrounds her, including the feelings and character of the people with whom she lives.

This attitude is born with the child. She must not have learned it from adults, because in our world the presence of distrust, insecurity and fear is remarkable. According to Luíza Lameirão “imitation, therefore, is the first form of learning that human beings already bring with them. , for still being immersed in the world from which I came. We can say that imitation is a bodily memory that is lived in unconsciousness or semi-consciousness.”(6) Thus, every child, in their impulse to act in this world where they arrived, starts from the assumption that it is moral, worthy of being imitated. .

“Before the change of teeth, the child is still inserted in the past, is still filled with that dedication that develops in the spiritual world. That's why he also surrenders to his environment by imitating people. What, then, is the fundamental impulse, the still totally unconscious basic disposition of the child until the change of teeth? It is a very beautiful disposition, which must also be cultivated – one that starts from the assumption, from the unconscious assumption that the whole world is moral.”(8) Rudolf Steiner

Thus, according to Waldorf Pedagogy, the first question that a child educator should ask himself is: Am I a person worthy of imitation? Am I loving, understanding and patient with children? Do I have enthusiasm and dedication for what I do? Am I consistent in my attitudes? At this stage, it is not what we say to the child that he assimilates, but how we behave in front of him. The pure and dedicated way in which the small child gives himself to the world is equivalent to the devotion of a religious man. It is this natural veneration for the world that surrounds them that we must take advantage of to show the child, always through images, that “the world is good”, and create spaces for them to explore it in their fantasies and games.

second seven years

The most beautiful thing that can be provided to the child at school, for later life, is the most varied and comprehensive idea possible of man. Rudolf Steiner

We have seen that, from the point of view of Waldorf Pedagogy, in the first seven years the “gateway” to education is the child's desire, and that his learning happens, basically, by imitation. In the second seven years, this entry is made through feeling, because at this stage effective learning occurs from the experience of the contents. After the change of teeth, a period that coincides with the beginning of elementary school, the child has new faculties. While in the first seven years, the mental representations that the child made when listening to a story lasted only while the story was told, now they start to act more constantly, and become the foundation for the child's memory(9). At this stage the child is very receptive to images, and any material must first be presented in the form of images. The child evolves during this period towards an increasingly abstract thinking, but the transformation of images and phenomena into concepts and rules must proceed gradually.

“If we inoculate a nine- to ten-year-old child with concepts destined to be present in a man at the age of thirty, forty, then we inoculate him with conceptual corpses, because the concept does not live together with man as he develops. We must offer the child concepts that in the course of his life can be transformed […] By doing so, we will be inoculating the child with living concepts. Therefore, in Waldorf Pedagogy, during the second seven years, definitions and concepts by heart are avoided and characterization is worked on.”(10) Rudolf Steiner

Thus, the planning of elementary education in Waldorf Pedagogy is done by tracing a path that leads from image to concept, from perception to understanding. This evolution towards conceptualization must accompany the development of the student's potential, so that his interest in the class is always maintained. First he must understand the general aspects, to later understand the particularities and the relationships between them, and then be able to elaborate syntheses through his thinking. Thus, all contents worked from images and experiences by young children will be elaborated again when they are older, in conceptual and scientific terms. This long-term vision permeates curriculum planning, and learning must always have experience as a starting point.

Jon McAlice states that “the transition from image to concept, as referred to in Waldorf Pedagogy, is the basis for the development of a way of thinking that, free from prejudice, seeks to discover the world”(11). If we try to remember remarkable facts that occurred in school, in our childhood, we will realize that what marked us were those that touched us by emotion, by feeling. Therefore, at this stage, the main “gateway” to learning is the emotional experience of the contents, as the child here still does not naturally relate to a purely intellectual approach. Subsequently, memory is strengthened through the use of imagination, and can recreate what had been perceived by the senses and transform it in conceptual terms.

Lanz also states that the precocious conceptualization, in the child, is one of the causes of the massification of society. The less developed the ability to abstract, to arrive at the concept, the more ready-made ideas are accepted. In a direct criticism of conventional education, the author argues that “ready, undigested concepts are one of the causes of massification, as there was no individual abstracting effort on the part of the child to reach the final goal of the concept based on their experiences of concrete situations”. (12)

The anthropological view, which underlies Waldorf Pedagogy, considers that human development evolves from the total unconsciousness of the newborn to the total consciousness of the 21-year-old, going through a period of “semi-consciousness” that coincides with that of elementary school, when, through the adult, the child must have a subjective experience of the world, based on their own emotions, feelings and thoughts.

the world is beautiful

The expectation of the healthy child, in the second seven years, is that the world will be beautiful. His great natural enthusiasm makes this very clear. It is up to the educator to face the great challenge of presenting the child with a world worthy of their admiration, in an artistic and creative way, and based on a caring authority. This authority, based on respect and admiration, should be the mainstay of education throughout the second seven years. While the child, in the first seven years, was totally open to the influences of the world around him, from the change of teeth and until around the age of 9, he starts to have a barrier between his inner and outer world, covered by the colored veil of her own fantasy, from which she manages her relationships. The outside world no longer enters freely, it has to conquer the child.

Lievegoed says that the child “is attracted to people who paint conceptual images in words and whose caressing and uplifting voice is capable of narrating a truly beautiful story”. He also considers that “for the child, the problems of his infantile kingdom are extremely serious, constituting a training for the true later life. Just as a small child needs material to exercise his hands, so a school-age child needs exercise material for his entire soul life, not just for the intellect department (emphasis by the author).”(13)

The child in the second seven years has great joy and wants the world to be presented to him in a playful and lively way. The main characteristic of the phase between 7 and 9 years of age is the great willingness to learn, without the need to make judgments. At this stage, children have a good memory, a lot of imagination, they like activities with rhythmic repetitions and narratives that arouse fantasy.

During the age of 7 and 8, the child still does not separate his “I” from the world. She feels one with him. It is from the age of 9 that she begins to perceive herself as an “I” separate from her environment, and this causes a profound change in her behavior. It becomes more insecure, angry and critical, and unimaginative. Unconsciously begins to question the teacher's authority. Before, she could love him unconditionally, but now she must earn genuine respect in his ability to present the world to him, and in his ethical and moral strength. Passerini clarifies that:

“At this time, the objectification of feeling takes place, translating into the experience, first sporadic, then more intense, of loneliness, which extends until puberty. Paradise is lost and, with it, naivety. She sees the world as Adam and Eve, expelled from Eden, seeing it for the first time (emphasis by the author)”.(14) Sueli Passerini

The more this loss is felt by the child, the more important it is for the teacher to become a reference center for them. Around the age of 10, when the child is already more adapted to their own individuality, a more harmonious phase begins, which should last until the age of 12. She is very active and interested. His inclination to criticism increases and his respect and veneration for the adult, and for the teacher, will depend on their moral authority. The lack of having human figures in which to place their respect makes young people seek their ideals in fantastic and fictional heroes, especially in video games, television and cinema. Lanz believes that until the age of 14, the young man is an idealist. “They hope to find ideals and see them realized; first, human ideals. If we fail to respond to this idealism through forgetfulness, ignorance or cynicism, something will definitely be destroyed in the young person's soul.”(15) Before puberty, morals should not be taught abstractly, based on theoretical precepts; must be experienced. Good must please and evil must disgust.

Another important characteristic of children at this time is their greater capacity for reasoning, their intellectuality, which then needs to be guided and nurtured by the teacher. With puberty approaching, young people lose their grace, and the pleasure of opposing grows.

“The profound internal transformation that appears as an accompaniment to physical puberty casts its shadows ahead, but also its light: there are forces of understanding and a sense of responsibility, which the teacher only needs to stimulate, to see the beauty and strength of this stage of life emerge. life! Loneliness and authentic friendship, self-centeredness and selfless interest in everything, love and death – hitherto in the unknown depths of feeling – become totally personal experiences. Independent feelings awaken, transform the relationship with one's own body, with the environment, with ideas and ideologies; is reflected both in an interest in the world and in the capacity to love, as well as in the need to examine causes and effects and to pass judgment.”(16) Carlgren and Kingborg

The second seven years culminates with puberty, a period of profound changes, both physical, emotional and intellectual. Teachers Cristina Ábalos, Dora Garcia and Vilma Paschoa affirm that there is a gradual loss of body harmony, and a great energy is manifested, especially in boys, who need appropriate activities to give it vent. Girls, in turn, show instability in their sentimental experiences. At the same time, young people begin to want to conquer the world, to experience their own power, which can lead to wild and unrealizable projects. They also want to know how the world works and seek to understand everything through reason and logic. To deal with all these transformations, the educator's task is to lead the young person to the autonomy of judgment, to make him capable of judging reality, so as not to be defenseless and subject to all kinds of external influences.(17)

third seven years

In this period, which begins in adolescence and goes until adulthood, the “gateway” of education is thinking. The young person now really wants to know what the teacher knows about each subject, and wants to conquer the world of ideas. Becomes ruthlessly critical and takes pleasure in questioning the opinions of others and questioning their motives. Thus, the principle of authority, which was the keynote during the second seven years, therefore ceases to have any value during the third. On the contrary, by forcing any authority without having a just reason for doing so, the teacher provokes an attitude of revolt.

the world is true

While in the first seven years, in Waldorf Pedagogy, the message of education should be that “the world is good”, and in the second set, that the “world is beautiful”, in the third set, it should be that “the world is is true". It is the period of some disappointments, when the young person perceives defects in people where he did not notice them before, because now he wants the real world. The lack of understanding and the gap that opens between generations often stem from the difficulty that adults have to live up to the ideal image that young people unconsciously made of them. About the third seven years, Melanie Guerra, Alfredo Rheingantz and José Maiolino explain:

“In this period of life and learning, self-judgment leverages the critical spirit, changing young people's relationships with themselves and with the world. The revolt against existing authority and values gains strength. Waldorf Pedagogy establishes important foundations for this phase of human development. Respect for individuality helps to bridge the apparent gaps of incomprehension between generations. From the 9th to the 12th grade, it is up to the students to assume the commitment of their own learning. Freedom must rhyme with responsibility […] The fundamental pedagogical principle here is the recognition of the educator's qualities, especially his intellectual capacity and moral integrity”.(18)

If the education of this young person has evolved harmoniously, he will be able to face this turbulent phase of puberty with more balance, to experience the world with a conscious and positive attitude, and to learn to think autonomously through a scientific understanding. According to Waldorf Pedagogy, it is important that your thinking and your conscience have not been distorted in the previous seven years, forced into an early maturation.

All school education work, according to Lanz's opinion, should culminate in the formation of young people with a thinking guided by a serene desire, a desire tamed by an intelligent discernment, all of this permeated with strong but not selfish feelings. The ideal that the educator should aim for is that, “instead of leaving school with a head full of information and a heart full of boredom, the teenager should be trained in the sense of wanting, with all the fibers of his personality, to give a contribution to the progress of the world.”(19)

Here is a summary made by Lievegoed about the phases of human development, according to the anthropological view that underlies Waldorf Pedagogy:

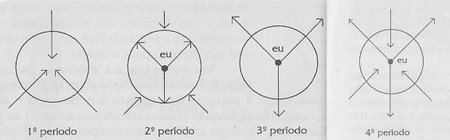

1) First Septennium: The most important relationship with the outside world takes place from the outside in, but the experiences acquired in this period are not yet self-centered.

2) Second seven years: The child is a closed unit. Starting from the self as the center, your forces work all the way to the periphery of your little kingdom. The outside world no longer enters unhindered; it just leaves impressions at the edge of that realm, which are absorbed only after going through a “process of assimilation”.

3) Third Septennium: The main direction is from the inside out. The outside world needs to be conquered and transformed.

4) Majority: It is only now that the outside world re-enters its interior, as the human being opens up to it again, and the one-sided direction of activity comes into balance. This is what leads to life experience.(20)

Graphic - The meaning of relationships between human beings and the world

Bibliography

- LANZ, Rudolph. Waldorf Pedagogy, 1990, p. 34.

- CARLGREN, Frans and KLINGBORG, Arne. Education for Freedom – the Pedagogy of Rudolf Steiner. 2006, p. 25.

- LIEVEGOED, Bernard. Uncovering Growth. 1994, p. 38.

- CRAEMER, Ute, co-author of 'Transforming is Possible' and author of 'Children between Light and Shadows', Ed. Monte Azul, Waldorf teacher, founder of Associação Monte Azul and Aliança pela Infância do Brasil.

- STEINER, Rudolph. Walk, Talk, Think. 2007, p. 19.

- LIEVEGOED, Bernard. Uncovering Growth. 1994, p. 13.

- LAMEIRAO, Luiza Tannuri. Child playing! Who educates her? 2007, p. 12.

- STEINER, Rudolph. The Art of Education I. 2007, p. 113.

- BIEKARCK, Peter. Video Collection Great Educators. 2009

- STEINER, Rudolph. The Art of Education I. 2007, p. 111.

- MCALICE, Jon and GÖBEL, Nana, et al. Waldorf Pedagogy – UNESCO, 1994, p. 32

- LANZ, Rudolph. Waldorf Pedagogy. 1990, p. 54

- LIEVEGOED, Bernard. Uncovering Growth. 1994, p. 64.

- PASSERINI, Sueli Pecci. Ariadne's Thread: A Path to Storytelling. 1998, p. 58.

- LANZ, Rudolph. Waldorf Pedagogy. 1990, p. 46.

- CARLGREN, Frans and KLINGBORG, Arne. Education for Freedom – the Pedagogy of Rudolf Steiner. 2006, p. 138.

- SALES, Ruth. Theater at School – vol.5. Pedagogical guidelines by Cristina MB Ábalos, Dora R. Zorsetto Garcia and Vilma L. Furtado Paschoa. 2007, p. 15.

- GUERRA, Melanie and RHEINGANTZ, Alfredo and MAIOLINO, José (orgs). Waldorf Pedagogy – 50 Years in Brazil: 2006, p. 26.

- LANZ, Rudolph. Waldorf Pedagogy. 1990, p. 50.

- LIEVEGOED, Bernard. Uncovering Growth. 1994. p.15.

***